Reposted from The Guardian

In 2003, with just a few hundred pounds, actor Femi Oguns set up Britain's first 'black' drama school. It's now a powerhouse in the promotion of black talent to the entertainment industry here and abroad.

Sandwiched between a hipster pub and an empty shop front, you are likely to hear the Identity Drama School in east London before you see it. As I loiter outside, the passing traffic is punctuated with the hubbub of student recitals, which filter down from the window above. It may not compete with Rada's lavish Bloomsbury setting or Lamda's 150-year-old history, but what goes on behind these walls serves an arguably more vital and immediate purpose than any of the country's more established drama schools.

Inside, a class of students line up, their backs pushed up against the walls of the studio, the room already thick with the warmth and odour of hard work. "In," bellows the vocal coach as he strides around the space. The students inhale. Eyes shut. Focused. He counts four beats. "Out," he says. The students exhale. "Sha," he calls. "Sha," they reply in unison. It's a fairly routine vocal warm up, so what is going on here that's unique?

It's simple. All the students present are black. Set up eight years ago, Identity is Britain's first "black" drama school and, partnered with its talent agency, IAG in Covent Garden, and a sister school in Birmingham, is fast becoming a powerhouse in the promotion of black and minority ethnic talent to the entertainment industry, both at home and abroad.

Sitting beside me as we observe the vocal coaching, which has now progressed from breathing to enunciation – "from the banks of Miss-iss-ip-pi to the Lake Ti-ti-ca-caa," – is founder of the school and agency CEO, Femi Oguns. An actor by training, Oguns set up the school in 2003 with a few hundred pounds he had set aside, a fistful of flyers and a dedicated vision.

"It has that Hollywood rags-to-riches feel about it, I guess," he says. "When I started, I got students by handing out flyers in areas such as Stratford, Hackney, Islington and Brixton, offering drama classes for free. I remember writing on the flyer, 'Would you like to be taught by acting coaches who've acted in EastEnders, Prime Suspect, Silent Witness, The Bill?' And in reality, there was only one acting coach, and that was me."

Now the schools boast a collective intake of 350 pupils, aged between 12 and 60 (and a range of ethnicities), but is yet to receive a penny of public funding. We flit around the building's four studios, gatecrashing improvisations, rehearsed readings and experimental sessions as we go.

All the students wear uniforms bearing the school's emblem, with "actor" emblazoned in bold on the back. It is a well-oiled machine and a calm respect exudes from pupils and teachers when Oguns walks into each room. "A disciplined environment is a creative one," he says.

So why the need to set it up in the first place? Oguns, 34, who grew up in west London, is convinced that there is a deficit in the minority talent being picked up by mainstream drama schools, and that which is left remains untrained.

"For me it begged the question: what happens to the others who don't get in? Rather than dwelling on it for too long, I decided to set up a school. I was always brought up with the philosophy of not waiting for change to happen, but creating it instead."

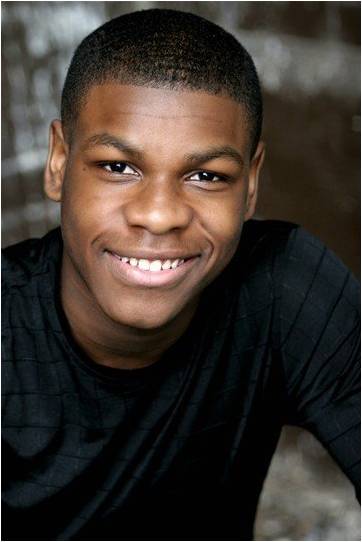

Identity student John Boyega who recently starred in British film 'Attack the Block'

Identity's most recent success story is that of 19-year-old John Boyega, who has just landed the lead in Spike Lee's forthcoming HBO drama Da Brick, but there is a sense the industry itself is not managing to keep up with the strides being made here in Hackney. Earlier this month David Harewood, a lead in US conspiracy drama Homeland that aired for the first time in the UK on Sunday (19 February), reinforced a view that has long been espoused by minority performers frustrated with the lack of opportunities on offer here: "There really aren't enough strong, authoritative roles for black actors in this country," he told a crowded Bafta screening at the British industry's grand epicentre in Piccadilly. "A lot of my contemporaries have gone to the US. I would encourage young black British actors to get to America if they have ambition."

His comments commanded headlines but frustrated Harewood, who tells me the broader, more nuanced point he was making got lost in a flurry of sensationalist stories. "It was reported as if I was saying they should leave the UK and just go to America straight away. That's an oversimplification. What we have here is fantastic training, like Femi's place, and in theatre we've seen colourblind casting for many years. You can see great examples of black actors playing classical roles, from Chekhov right through to Shakespeare. But in television that's just not happening…There are thousands of stories out there that are still not being told and I understand the frustrations of young boys who don't just want to be the next kid from the block."

It's worth noting that the US industry is not beyond reproach. Indeed, if Viola Davies wins the best actress award at the Oscar for The Help she will be only the second African-American woman in history to do so. Earlier this week Denzel Washington derided an academy voting constituency that is 94% white, while fewer than 4% of awards go to African Americans.

Over here, Bafta says it doesn't keep a record of the ethnic makeup of its membership, although, under a newly formed diversity pledge, it plans to monitor it for the first time this year. It also says it does not keep a record of the numbers of British minority talent winning the big awards, although a quick flick through past winners in the actors and actresses categories shows that it is embarrassingly low; if Thandie Newton and Ben Kingsley were not around, it may well have constituted a snub.

Just who wins and who misses out on the film industry's big nights could be dismissed as an aside, but Bafta rising star award-winner Noel Clarke thinks there is a lesson to be learned. "I got the rising star award, and Adam [Deacon, writer/director/star of Anuvahood] got it a week ago, but here's the thing. The reason we win it is not because the industry loves us, it's because people do. If those awards weren't a public vote, then I probably wouldn't have won it. What happens in this country is the industry are so in love with certain people that they ignore what the public want."

Broadcasters and production companies are touchy when asked about their policies on inclusion. "Nobody wants to talk about it," says Harewood, "and I'm not surprised because it's such a lightning rod, as I found out for myself." But the successes of Harewood and Clarke are evidence enough that the industry is not impenetrable, Clarke's rise being tied to the fact that he writes and directs as well: "If I didn't start writing, I'd probably be homeless, or I would have moved here (Clarke is talking to me from LA, where he is filming the next instalment of JJ Abrams' Star Trek) a long time ago."

Noel Clarke's 'The Knot'

He often feels the same prejudice from the industry when submitting scripts, however – he was writing romcoms and sci-fi films at the same that he got his first writing break with urban drama Kidulthood. Reception for a new project, The Knot, in which he plays a romantic lead was initially lukewarm: "[I was told] it'd never get made because I was playing a best man at a wedding. The reaction was: 'That's ridiculous, why would you be playing a best man at a middle-class, white people's wedding?'"

For Clarke, however, such an attitude only inspires him to create more, with the portrayal of black and minority characters often at the forefront of his mind. "I could quite easily make those sorts of hood films. I could write them all day long, knock them out, cream off money, but it's not going to help the young actors of the future. When I do films like the ones coming out this year, Fast Girls (a sports drama that features four black female leads) and The Knot, I hope it helps the community. Me doing this now means that some kid in five years' time can walk into a room with a script about fairies and say, I want to write, direct and star in it, and they'll have to take it seriously."

For Harewood and Clarke, there's both optimism and chagrin in equal amounts, so where does this leave the new talent being produced in places such as Identity?

In the office, wedged between the two main studios, I sit down with three of Oguns' up and comers. All are upbeat about their prospects. "I want to make history," says 23-year-old Adelayo Adedayo, from Dagenham, currently filming the lead in a new BBC comedy. "A lot of the time people ask me: 'Who's your role model?' – and it throws me because when I try to think of someone on telly who looks like me, and is a household name, there really isn't. I want to be that person for other girls. What better way to break boundaries than by doing something you love?"

Malachi Kirby, 22, from Croydon, is still sweating from the vocal class that I sat in on earlier. His voice is tired, he is in the middle of shooting a feature film, but comes to class anyway – such is the dedication expected. "You're always going to have typecasting, especially with TV. But what Femi has taught me is that it's not the role that you get, but what you do with it. If you're good enough to play a role with emotion and universal human elements, then you'll get others coming to you."

And what about the prospect of heading to the US? Adedayo and Kirby have both been, taken there by Femi a few months ago. Twenty-two-year-old Tobi Bakare from Hackney went as well; he joined Identity when it first started and is set to play the guest lead in a double episode of Silent Witness next month. He is animated when describing the training he is getting here in method and Lecoq, but it is when he is talking about the sort of jobs he went up for in the US that he reaches full flow.

"I've never been a fan of the glitz and glamour, but it's very fast there and I like it. I had meetings with all sorts of people and I'm going up for roles that are so chunky so …" he pauses for a minute and apologises for getting too passionate. "But just so juicy!" He continues. "Sailors, older characters, younger characters. Parts that I believe I would be totally disassociated with in this country."

For Adedayo, the difference between here and the US is obvious: "People need to take more risks in the UK. [In the US] it wasn't stuffy or done by the book, the feeling was just, 'Let's throw it out there'. Here, people say we need to do things the way we've always been doing things, 'Let's just be careful'. Careful's not fun."

As I'm ushered out, a fresh group of students wait outside, ready for the day's second training session. With plans afoot to set up a school in LA, Ogun remains positive that there is change coming, but adds: "We're tired of just picking up the crumbs. We want to use them to make a cake for ourselves."

Congrats to Femi and all involved with Identity on their success so far.

For regular news, updates and opportunities, follow us on Twitter at @Scene_TV and 'Like' the Facebook page: www.facebook.com/SceneTV